The stark prospect of the timber on which the town was founded running out was what drove the construction of the Ohakune Mountain Road. Hugh de Lacy tells its story.

The railway through the central North Island had been finished, and the native timber industry that grew from it was running out of resources. So it seemed that the mountain town of Ohakune was doomed to permanent decline, like Raetihi, its sister town on the south edge of the central North Island volcanic plateau.

Local industries and the workforce had been reduced from the 1500 who had built the railway and the hundreds more who had harvested the magnificent podocarp forests, to the few hundreds involved in pastoral farming and the embryonic market gardening industry, the latter pioneered by former Chinese railway workers.

The question facing the Ohakune Borough Council was what to replace the old industries with.

Much head-scratching around the council table from the early 1900s onwards had drawn the conclusion that the only thing Ohakune had going for it, other than the railway station a couple of kilometres from the town, was the mountain that reared up over it to the north.

Stifling their fears of the Yellow Peril by leasing little parcels of land to Chinese railway workers was helping establish a horticulture industry, but in the long-term the mountain, tourism and skiing were seen to be its only salvation.

The first settlers had arrived in the area in 1892, having come up the Whanganui River to Pipiriki, then across to Raetihi and so on to Ohakune.

By 1896 there were still only 20 permanent residents in Ohakune, but over the next 12 years as the North Island Main Trunk railway line neared completion, and as saw-milling prospered, it had ballooned to 600.

By 1909 the sawmills were pumping out 9000 linear metres a day but this rate of harvest could not be sustained, and already there was agitation to preserve at least some of the stands of native trees for posterity.

The following year the Ohakune-Ruapehu Alpine Club was formed from locals and visitors keen to enjoy the 500 hectares of skiable slopes at Turoa, a thousand metres above the township.

So the members started building a walking track to the ski-fields, and within 12 years this had been expanded to a horse trail, and the first hut was built just below the snow-line.

A little later, in 1929, Ohakune had been temporarily blind-sided by the Tongariro National Park Board allowing the Chateau Tongariro to be built below the rival ski slopes at Whakapapa, on the western side of the mountain.

This prompted a series of petitions from Ohakune residents and the alpine club for a road, similar to the Whakapapa one, to be built to Turoa.

A decade and a half of fruitless agitation finally prompted the formation of the Ohakune Mountain Road Association, which set about, with the park board’s permission, building a road along the horse-track.

The remarkable thing about the road that began to inch its way up the mountain was that, until it was three-quarters finished, it was accomplished almost entirely by volunteer labour and local fund-raising: the Government chipped in with money only towards its completion.

The Ohakune road-makers were challenged early on by rival roading projects at Horopito, since famed for the Cole family’s vast car wrecking yard that was the scene of the hit Bruno Lawrence film “Smash Palace.”

Mainly Whanganui interests wanted the road to the Turoa ski-fields to go through Horopito so traffic to it from the south would have to pass through Whanganui and on up the Parapara highway (SH4).

Just to the east of Ohakune was the even tinier township of Rangataua whose residents wanted the road to go through their territory, and they were supported in this by the likes of the Taihape Borough Council, which was keen to see the ski-traffic come up SH1 through the Rangitikei rather than through Whanganui.

The Ohakune horse-trail did have some advantages over both Horopito and Rangataua, but the biggest was the commitment of the Ohakune people to their access route.

The construction of the Ohakune Mountain Road, which finally began by bulldozer, tractor, shovel and wheelbarrow in 1952, was a triumph of local organisation by families that included the Whales, Winchcombes, Goulds, Thompsons, Watsons, Berridges, O’Haras and Misheskis.

The club acquired its own Bedford truck, while Tim Whale lent a D4 bulldozer and his brother Wig a light truck and a small tractor.

At times it seemed like half the town turned out to push the road ahead “yard by yard” as they, and a small book on the project published in 2010, tell it.

Initial funding came from the hundred people who each donated £10 ($20) to a trust fund – an exercise repeated in 1960 – and from endless raffles, casino nights and even a visit from gameshow host Selwyn Toogood with his Lux soap-sponsored Money or the Bag show.

In the background there was constant, but largely unsuccessful lobbying of the Government and the then National Roads Board, but even though local MP Roy Jack and the National Party Minister of Works, Stan Goosman, lent their encouragement, it took 10 years to prise any money out of the Government.

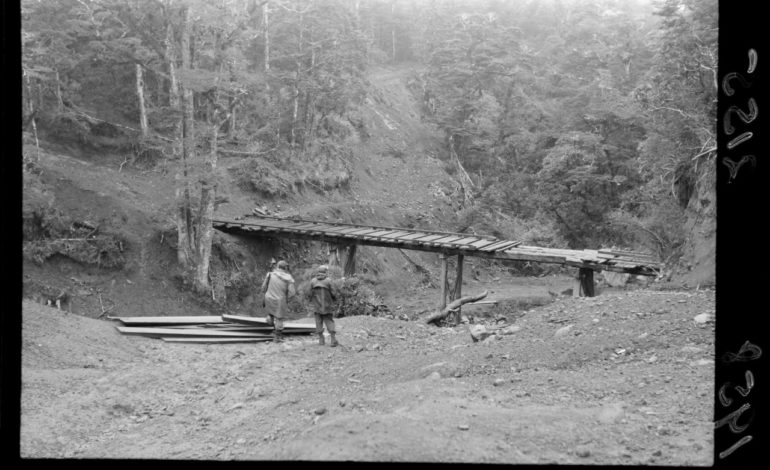

In terms of construction challenges the Ohakune Mountain Road was relatively easy, requiring only one culvert over Reid’s Creek – previously crossed by a wooden bridge further downstream – and one bridge over the Mangawhero River which in recent years has been expanded to two lanes.

There were boggy areas to cross above this bridge, and this was achieved by trucking up and hand-placing rocks, then metalling over them.

Excellent roading metal turned out to available at McLean’s Clearing, about seven kilometres up from Ohakune Junction, though the first over-enthusiastic effort to loosen the rock, by self-proclaimed explosives expert “Honey Bee” Watson, sprayed the bush with aggregate for a hundred metres around and initially left very little for the road.

But such setbacks were only to be expected by the amateur road-builders, whose efforts finally attracted enough Government funding to finish the project and lay the base for the subsequent development of the Turoa ski-field.

The first 12 kilometres of the road, as far as the Mangawhero Falls, was formally opened by Works Minister Goosman in March of 1963.

It took another five years for government funding to complete the remaining 5 kilometres.

The Ohakune Mountain Road was declared legal in 1976, and two years later the first ski-lift was installed at Turoa.

Today Turoa ski-field offers a 722 metre vertical drop served by no fewer than eight lifts capable of transporting 11,300 skiers an hour.

The timber milling is now just a different memory, and Ohakune is basking in the economic sunlight of a vibrant ski-based tourism industry.

Caption 1 : Bridge on the Ohakune Mountain Road, National Park part of Bridge on the Ohakune Mountain Road, National Park. Evening post (Newspaper. 1865-2002) :Photographic negatives and prints of the Evening Post newspaper. Ref: EP/1958/2155-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22698742

Caption 2 : Main Street, Ohakune – Photograph taken by William Beattie and Company, Auckland part of William Beattie & Company. Main Street, Ohakune – Photograph taken by William Beattie and Company, Auckland. Ref: PAColl-4601-12. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23193901

Parting words from Jeremy Sole- a final column